A warm hand has stretched out and taken yours. And somehow, the beauty of the writing can turn this message into something comforting. Yes, he seems to be saying, appalling things happen, unfair, unjustified, inexplicable, random things you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemy but there it is, we’re all in this together, that’s just the way it is.

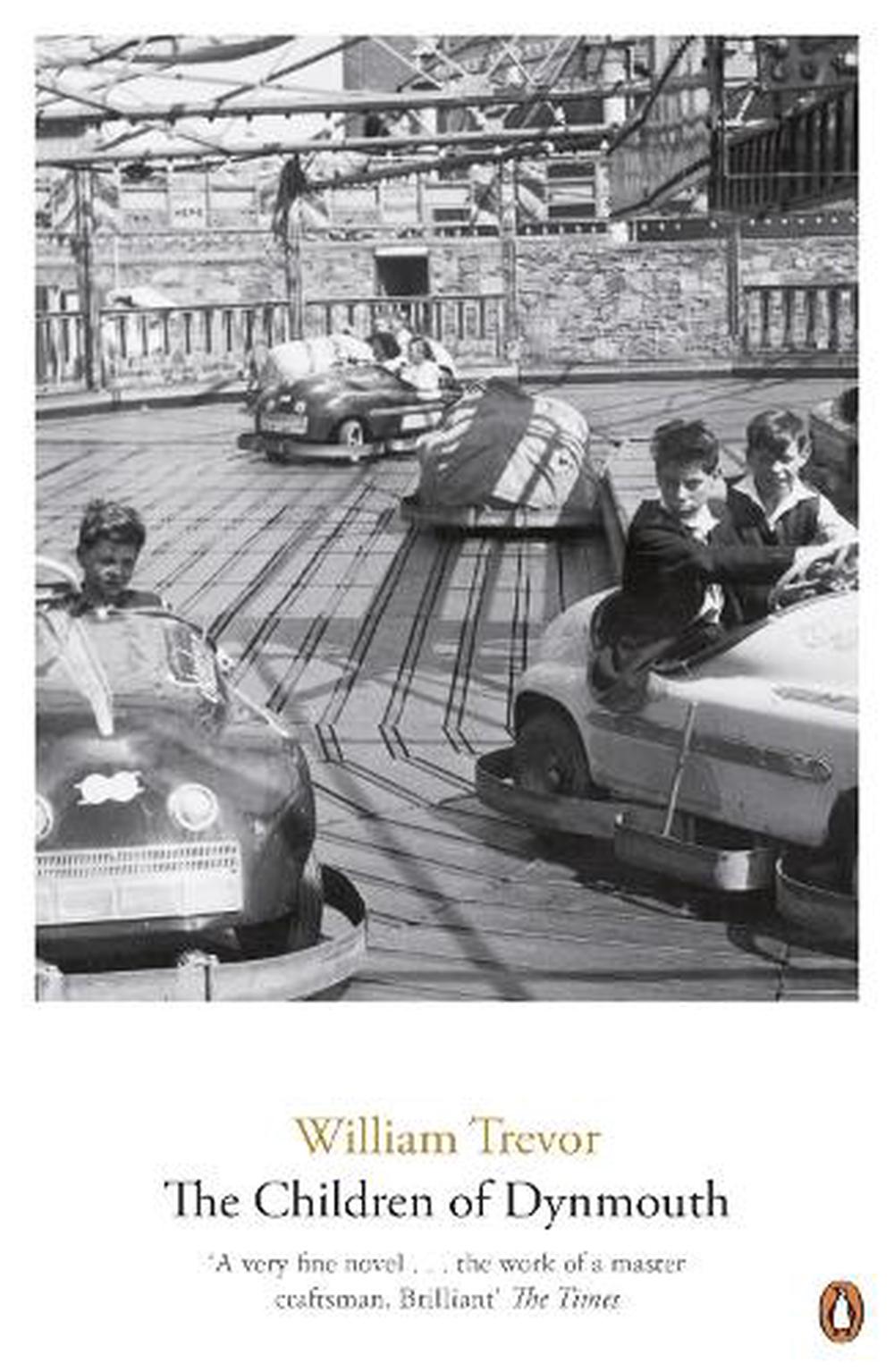

But one can definitely read him to be consoled: by the pin-point accuracy of the writing, by the absolute truth of his characters, by the universality of their predicaments, by the wisdom of his perceptions – in other words, by his humanity. One does not read William Trevor to be cheered up. I’ve been an ardent fan ever since, although I must admit that in one’s robust forties Trevor’s themes (sadness, loneliness, cruelty, the sheer arbitrariness of life’s awfulness) can be relished in a way that becomes increasingly difficult with age, as one’s skin thins and that arbitrariness begins to bite. I first came across William Trevor in the early nineties when my son came home from school with The Children of Dynmouth, his GCSE set text.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)